Building My Anti-library of Time

For years, my shelves of unread books felt like a burden—until I discovered the concept of the antilibrary. Now, they represent curiosity, humility, and potential. I’m building an antilibrary on time, inspired by thinkers like Hermsen and Hawking, and soundtracked by Canto Ostinato, my favorite meditation on timelessness.

6 meters of unred books

For years, a silent guilt clung to the six meters of bookshelf lining my walls, heavy with the weight of unread books. They stood there in silence, whispering judgments like: “Why did you buy me if you never intended to read me?” Each spine seemed to raise an eyebrow, each title a quiet accusation.

But I love them. I like how they look, how they feel, the smell of their pages and the possibility they carry. I bought them with good intentions: for rainy weekends and inspiring Sunday mornings, for future research projects that never come to pass. Still, they stand unopened. And so, the guilt builds up.

Until I discovered the concept of the antilibrary.

Tsundoku (積ん読)

The idea of the antilibrary entered my life through a reference to Umberto Eco—an intellectual giant known not only for his novels and academic works but also for his collection of over 30,000 books, many of which he had not read. Rather than viewing unread books as a failure, Eco considered them a source of knowledge yet to be discovered, a monument to intellectual humility.

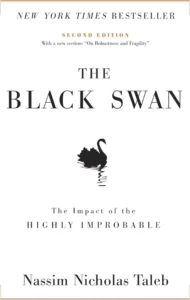

The concept was picked up and popularized by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in The Black Swan, where he praised the unread book as a symbol of what we don’t know, but could know. The antilibrary is not about hoarding knowledge—it’s about aspiring to it. It’s a personal research archive, a potential energy, a growing terrain of curiosity. It reminds us that knowledge is infinite—and that our own understanding is always incomplete. Each unread title is a doorway, not a dead end. In this light, the antilibrary becomes less a collection and more a conversation with the unknown

This idea transformed how I looked at my shelves. No longer did I see failure—what I see know is potential. Possibility. A map to yet-unexplored lands.

The Japanese even have a word for this: tsundoku. It refers to the habit of acquiring books and letting them pile up, unread. While it carries a hint of humor and self-deprecation, it also acknowledges something deeply human: we are more curious than we are capable of consuming. And that’s okay. Between tsundoku and the antilibrary, I found peace with my unread companions. They weren’t mocking me; they were waiting. Patiently.

Building an antilibrary around time

Lately, my antilibrary has begun to orbit around a single theme: time.

Time has always baffled and fascinated me. Not just as a ticking mechanism or an appointment on a calendar, but as a philosophical, cultural, and even spiritual construct. I find myself drawn to thinkers who explore it from vastly different perspectives, and so I started collecting them.

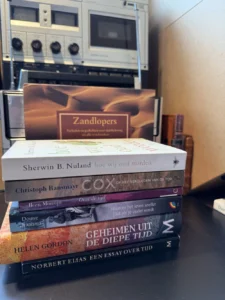

Among them:

- Joke Hermsen, who writes with lyrical depth about time, slowness, and art, particularly in relation to the music of Simeon ten Holt’s Canto Ostinato

- Norbert Elias, with his sociological exploration of how time is constructed socially

- Stephen Hawking, whose theoretical framework challenges everything we thought we knew about time’s direction

- Douwe Draaisma, a master of memory and temporality

- Ileen Montijn, whose work brings historical depth to our daily sense of time

- Christoph Ransmayr, whose storytelling feels drenched in geological time

- Sherwin B. Nuland, who examines time in the context of aging and dying

Each book adds a different tone to the chord of understanding—some poetic, some scientific, some melancholic. And yet, many of them are still unread. And that’s fine. That’s the whole point.

The Canto Ostinato: my Soundtrack to time

I listen to Canto Ostinato multiple times a week. Sometimes in the background while writing, other times fully immersed with noise-cancelling headphones. It’s a piece of music that, like time itself, shifts without seeming to move. The patterns return, repeat, slightly change, and then circle back.

Joke Hermsen wrote about Canto Ostinato as a musical expression of subjective time. “It doesn’t push forward—it expands inward.” The listener is invited into a state of duration, rather than progression. Time becomes space. This resonates deeply with the philosophical idea of kairos—time as qualitative, not quantitative.

“Time is a flame I hold in my hand.”

– Ancient Persian proverb (attributed to Zoroaster)

The Persian wisdom around time—cyclical, sacred, burning and luminous—offers a powerful contrast to our Western fixation on linearity and efficiency. Zarathustra (Zoroaster) and the Avesta speak of time not as something you spend, but something you inhabit, honor, and return to.

In a world obsessed with productivity, Canto Ostinato feels like a defiant act of lingering.

An open invitation

If you’ve ever felt guilty about buying books you haven’t read: don’t. You are building a living archive of your curiosity. You’re charting a map of what you want to understand—even if you haven’t reached the territory yet. My antilibrary now feels like a companion on the road, not a reminder of detours. Especially the part dedicated to time, which I hope to explore slowly, deliberately.

If you know of any books that delve into time – philosophically, culturally, scientifically, spiritually,- I’d love your suggestions and add them to the antilibrary.

Because in the end, perhaps the greatest luxury isn’t to conquer time, but to dwell in it. And if I ever get around to it, I may just start the Canto Ostinato Appreciation Society.

I think it’s time.